What Are Post Modern Values in Art? What Are Postmodern Values in Art?

Postmodern art is a trunk of art movements that sought to contradict some aspects of modernism or some aspects that emerged or developed in its aftermath. In full general, movements such as intermedia, installation fine art, conceptual art and multimedia, particularly involving video are described as postmodern.

There are several characteristics which lend art to being postmodern; these include bricolage, the use of text prominently as the cardinal artistic element, collage, simplification, appropriation, operation art, the recycling of past styles and themes in a modern-twenty-four hour period context, likewise every bit the break-upwards of the barrier between fine and high arts and low art and popular culture.[1] [ii]

Apply of the term [edit]

The predominant term for fine art produced since the 1950s is "contemporary fine art". Not all fine art labeled as contemporary art is postmodern, and the broader term encompasses both artists who go along to work in modernist and belatedly modernist traditions, as well every bit artists who turn down postmodernism for other reasons. Arthur Danto argues "contemporary" is the broader term, and postmodern objects correspond a "subsector" of the gimmicky motion.[3] Some postmodern artists have made more distinctive breaks from the ideas of modern art and there is no consensus as to what is "belatedly-modernistic" and what is "postal service-modern." Ideas rejected past the modern aesthetic have been re-established. In painting, postmodernism reintroduced representation.[iv] Some critics argue much of the current "postmodern" art, the latest avant-gardism, should still classify equally modern art.[5]

As well as describing certain tendencies of contemporary art, postmodern has also been used to denote a phase of modern art. Defenders of modernism, such every bit Clement Greenberg,[6] also equally radical opponents of modernism, such every bit Félix Guattari, who calls it modernism'southward "concluding gasp,[7]" have adopted this position. The neo-conservative Hilton Kramer describes postmodernism as "a creation of modernism at the end of its tether."[8] Jean-François Lyotard, in Fredric Jameson's assay, does non concord there is a postmodern phase radically unlike from the period of high modernism; instead, postmodern discontent with this or that loftier modernist style is part of the experimentation of loftier modernism, giving nativity to new modernisms.[9] In the context of aesthetics and art, Jean-François Lyotard is a major philosopher of postmodernism.

Many critics hold postmodern art emerges from modern art. Suggested dates for the shift from modern to postmodern include 1914 in Europe,[10] and 1962[xi] or 1968[12] in America. James Elkins, commenting on discussions about the exact appointment of the transition from modernism to postmodernism, compares information technology to the word in the 1960s about the verbal span of Mannerism and whether information technology should begin directly after the High Renaissance or subsequently in the century. He makes the indicate these debates keep all the time with respect to art movements and periods, which is not to say they are non important.[13] The close of the period of postmodern art has been dated to the finish of the 1980s, when the word postmodernism lost much of its critical resonance, and art practices began to accost the impact of globalization and new media.[14]

Jean Baudrillard has had a meaning influence on postmodern-inspired art and emphasised the possibilities of new forms of creativity.[15] The creative person Peter Halley describes his mean solar day-glo colours equally "hyperrealization of real color", and acknowledges Baudrillard equally an influence.[16] Baudrillard himself, since 1984, was fairly consequent in his view gimmicky art, and postmodern fine art in item, was inferior to the modernist art of the post World War Two catamenia,[16] while Jean-François Lyotard praised Contemporary painting and remarked on its evolution from Modern art.[17] Major Women artists in the Twentieth Century are associated with postmodern art since much theoretical articulation of their piece of work emerged from French psychoanalysis and Feminist Theory that is strongly related to mail service modern philosophy.[18] [19]

American Marxist philosopher Fredric Jameson argues the status of life and production will be reflected in all activeness, including the making of art.

As with all uses of the term postmodern there are critics of its application. Kirk Varnedoe, for instance, stated that in that location is no such thing equally postmodernism, and that the possibilities of modernism have not yet been exhausted.[xx] Though the usage of the term as a kind of shorthand to designate the work of certain Post-war "schools" employing relatively specific material and generic techniques has become conventional since the mid-1980s, the theoretical underpinnings of Postmodernism every bit an epochal or epistemic division are nevertheless very much in controversy.[21]

Defining postmodern art [edit]

The juxtaposition of old and new, especially with regards to taking styles from by periods and re-plumbing fixtures them into modern art outside of their original context, is a mutual characteristic of postmodern art.

Postmodernism describes movements which both arise from, and react against or reject, trends in modernism.[22] General citations for specific trends of modernism are formal purity, medium specificity, fine art for art's sake, actuality, universality, originality and revolutionary or reactionary tendency, i.e. the avant-garde. However, paradox is probably the most important modernist idea against which postmodernism reacts. Paradox was central to the modernist enterprise, which Manet introduced. Manet's various violations of representational art brought to prominence the supposed common exclusiveness of reality and representation, blueprint and representation, abstraction and reality, and then on. The incorporation of paradox was highly stimulating from Manet to the conceptualists.

The status of the avant-garde is controversial: many institutions debate being visionary, forward-looking, cutting-edge, and progressive are crucial to the mission of fine art in the present, and therefore postmodern fine art contradicts the value of "fine art of our times". Postmodernism rejects the notion of advancement or progress in art per se, and thus aims to overturn the "myth of the advanced". Rosalind Krauss was one of the important enunciators of the view that avant-gardism was over, and the new artistic era is post-liberal and mail-progress.[23] Griselda Pollock studied and confronted the avant-garde and modern art in a series of groundbreaking books, reviewing mod art at the same time equally redefining postmodern art.[24] [25] [26]

One characteristic of postmodern art is its conflation of high and depression civilisation through the use of industrial materials and pop culture imagery. The apply of depression forms of art were a part of modernist experimentation besides, as documented in Kirk Varnedoe and Adam Gopnik'south 1990–91 show High and Depression: Pop Civilisation and Modern Art at New York's Museum of Mod Art,[27] an exhibition that was universally panned at the time as the just event that could bring Douglas Crimp and Hilton Kramer together in a chorus of contemptuousness.[28] Postmodern art is noted for the way in which it blurs the distinctions betwixt what is perceived every bit fine or loftier fine art and what is generally seen every bit low or kitsch art.[29] While this concept of "blurring" or "fusing" high art with low art had been experimented during modernism, information technology only ever became fully endorsed later on the advent of the postmodern era.[29] Postmodernism introduced elements of commercialism, kitsch and a general camp artful within its artistic context; postmodernism takes styles from past periods, such as Gothicism, the Renaissance and the Baroque,[29] and mixes them so equally to ignore their original employ in their corresponding artistic movement. Such elements are common characteristics of what defines postmodern art.

Fredric Jameson suggests postmodern works abjure any claim to spontaneity and directness of expression, making use instead of pastiche and discontinuity. Against this definition, Fine art and Language's Charles Harrison and Paul Wood maintained pastiche and aperture are endemic to modernist art, and are deployed effectively by modern artists such as Manet and Picasso.[30]

One compact definition is postmodernism rejects modernism's grand narratives of artistic direction, eradicating the boundaries between high and low forms of art, and disrupting genre's conventions with collision, collage, and fragmentation. Postmodern fine art holds all stances are unstable and insincere, and therefore irony, parody, and humor are the but positions critique or revision cannot overturn. "Pluralism and diversity" are other defining features.[31]

Avant-garde precursors [edit]

Radical movements and trends regarded every bit influential and potentially equally precursors to postmodernism emerged around Globe War I and particularly in its aftermath. With the introduction of the use of industrial artifacts in art and techniques such as collage, avant-garde movements such as Cubism, Dada and Surrealism questioned the nature and value of fine art. New artforms, such equally cinema and the rise of reproduction, influenced these movements equally a means of creating artworks. The ignition point for the definition of modernism, Clement Greenberg'south essay, Advanced and Kitsch, start published in Partisan Review in 1939, defends the avant-garde in the confront of popular culture.[32] Later, Peter Bürger would brand a distinction betwixt the historical advanced and modernism, and critics such every bit Krauss, Huyssen, and Douglas Crimp, following Bürger, identified the historical avant-garde as a forerunner to postmodernism. Krauss, for instance, describes Pablo Picasso'due south utilise of collage as an advanced practice anticipating postmodern art with its emphasis on linguistic communication at the expense of autobiography.[33] Some other indicate of view is avant-garde and modernist artists used similar strategies and postmodernism repudiates both.[34]

Dada [edit]

In the early 20th century Marcel Duchamp exhibited a urinal as a sculpture. His betoken was to have people look at the urinal as if it were a work of fine art just because he said it was a work of fine art.[35] [36] [37] He referred to his piece of work equally "Readymades".[38] The Fountain was a urinal signed with the pseudonym R. Mutt, which shocked the art world in 1917.[39] This and Duchamp'south other works are more often than not labelled as Dada. Duchamp tin be seen as a precursor to conceptual art. Some critics question calling Duchamp—whose obsession with paradox is well known—postmodernist on the grounds he eschews any specific medium, since paradox is not medium-specific, although it arose start in Manet's paintings.[xl]

Dadaism can be viewed as part of the modernist propensity to claiming established styles and forms, along with Surrealism, Futurism and Abstract Expressionism.[41] From a chronological indicate of view, Dada is located solidly within modernism, however a number of critics hold it anticipates postmodernism, while others, such as Ihab Hassan and Steven Connor, consider information technology a possible changeover point betwixt modernism and postmodernism.[42] For example, according to McEvilly, postmodernism begins with realizing i no longer believes in the myth of progress, and Duchamp sensed this in 1914 when he changed from a modernist practice to a postmodernist one, "abjuring artful delectation, transcendent ambition, and tour de force demonstrations of formal agility in favor of artful indifference, acknowledgement of the ordinary globe, and the establish object or readymade."[10]

Radical movements in modernistic fine art [edit]

In general, Pop Art and Minimalism began every bit modernist movements: a epitome shift and philosophical split between formalism and anti-ceremonial in the early 1970s caused those movements to be viewed by some as precursors or transitional postmodern art. Other modern movements cited equally influential to postmodern fine art are conceptual fine art and the employ of techniques such as assemblage, montage, bricolage, and appropriation.

Jackson Pollock and abstract expressionism [edit]

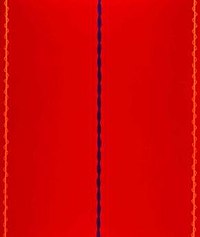

During the tardily 1940s and early on 1950s, Pollock'southward radical approach to painting revolutionized the potential for all Contemporary art post-obit him. Pollock realized the journeying toward making a piece of work of art was every bit important as the work of art itself. Like Pablo Picasso's innovative reinventions of painting and sculpture well-nigh the plow of the century via Cubism and constructed sculpture, Pollock redefined artmaking during the mid-century. Pollock's motion from easel painting and conventionality liberated his contemporaneous artists and following artists. They realized Pollock's procedure — working on the floor, unstretched raw canvas, from all four sides, using artist materials, industrial materials, imagery, non-imagery, throwing linear skeins of pigment, dripping, drawing, staining, brushing - blasted artmaking across prior boundaries. Abstruse expressionism expanded and adult the definitions and possibilities artists had available for the cosmos of new works of fine art. In a sense, the innovations of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, Philip Guston, Hans Hofmann, Clyfford Nevertheless, Barnett Newman, Advertizement Reinhardt and others, opened the floodgates to the diversity and scope of following artworks.[43]

Later abstract expressionism [edit]

In abstract painting during the 1950s and 1960s several new directions like Hard-edge painting and other forms of Geometric abstraction like the piece of work of Frank Stella popped up, as a reaction against the subjectivism of Abstract expressionism began to appear in artist studios and in radical avant-garde circles. Clement Greenberg became the voice of Post-painterly abstraction; past curating an influential exhibition of new painting touring important art museums throughout the Usa in 1964. Color field painting, Hard-edge painting and Lyrical Abstraction[44] emerged equally radical new directions.

By the late 1960s, Postminimalism, Process Fine art and Arte Povera[45] also emerged equally revolutionary concepts and movements encompassing painting and sculpture, via Lyrical Abstraction and the Postminimalist movement, and in early on Conceptual Art.[45] Process fine art every bit inspired past Pollock enabled artists to experiment with and make use of a various encyclopedia of style, content, material, placement, sense of time, and plastic and real infinite. Nancy Graves, Ronald Davis, Howard Hodgkin, Larry Poons, Jannis Kounellis, Brice Marden, Bruce Nauman, Richard Tuttle, Alan Saret, Walter Darby Bannard, Lynda Benglis, Dan Christensen, Larry Zox, Ronnie Landfield, Eva Hesse, Keith Sonnier, Richard Serra, Sam Gilliam, Mario Merz, Peter Reginato, Lee Lozano, were some of the younger artists emerging during the era of late modernism spawning the heyday of the art of the late 1960s.[46]

Operation fine art and happenings [edit]

During the late 1950s and 1960s, artists with a wide range of interests began pushing the boundaries of Contemporary art. Yves Klein in France, and Carolee Schneemann, Yayoi Kusama, Charlotte Moorman, and Yoko Ono in New York City were pioneers of performance based works of art. Groups similar The Living Theater with Julian Brook and Judith Malina collaborated with sculptors and painters creating environments; radically irresolute the human relationship betwixt audience and performer especially in their piece Paradise Now.[48] [49] The Judson Dance Theater located at the Judson Memorial Church, New York, and the Judson dancers, notably Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Elaine Summers, Emerge Gross, Simonne Forti, Deborah Hay, Lucinda Childs, Steve Paxton and others collaborated with artists Robert Morris, Robert Whitman, John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, and engineers similar Billy Klüver.[50] These performances were often designed to be the creation of a new art form, combining sculpture, trip the light fantastic, and music or sound, often with audition participation. The reductive philosophies of minimalism, spontaneous improvisation, and expressivity of Abstract expressionism characterized the works.[51]

During the aforementioned menstruum — the late 1950s through the mid-1960s - diverse advanced artists created Happenings. Happenings were mysterious and ofttimes spontaneous and unscripted gatherings of artists and their friends and relatives in varied specified locations. Often incorporating exercises in absurdity, concrete exercise, costumes, spontaneous nudity, and diverse random and seemingly disconnected acts. Allan Kaprow, Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik, Wolf Vostell, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Scarlet Grooms, and Robert Whitman among others were notable creators of Happenings.[52]

Assemblage fine art [edit]

Related to Abstract expressionism was the emergence of combined manufactured items — with creative person materials, moving away from previous conventions of painting and sculpture. The work of Robert Rauschenberg, whose "combines" in the 1950s were forerunners of Pop Fine art and Installation fine art, and fabricated use of the aggregation of large physical objects, including stuffed animals, birds and commercial photography, exemplified this art trend.[ citation needed ]

Leo Steinberg uses the term postmodernism in 1969 to describe Rauschenberg's "flatbed" picture plane, containing a range of cultural images and artifacts that had not been compatible with the pictorial field of premodernist and modernist painting.[53] Craig Owens goes farther, identifying the significance of Rauschenberg's work not as a representation of, in Steinberg'south view, "the shift from nature to culture", just every bit a demonstration of the impossibility of accepting their opposition.[54]

Steven Best and Douglas Kellner place Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns as part of the transitional phase, influenced by Marcel Duchamp, betwixt modernism and postmodernism. These artists used images of ordinary objects, or the objects themselves, in their work, while retaining the abstraction and painterly gestures of high modernism.[55]

Anselm Kiefer too uses elements of assemblage in his works, and on one occasion, featured the bow of a fishing boat in a painting.

Pop art [edit]

Lawrence Alloway used the term "Pop art" to describe paintings jubilant consumerism of the post World War II era. This motion rejected Abstruse expressionism and its focus on the hermeneutic and psychological interior, in favor of fine art which depicted, and often celebrated, material consumer civilisation, advertising, and iconography of the mass production age. The early on works of David Hockney and the works of Richard Hamilton, John McHale, and Eduardo Paolozzi were considered seminal examples in the motility. While afterward American examples include the bulk of the careers of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein and his utilise of Benday dots, a technique used in commercial reproduction. There is a clear connection betwixt the radical works of Duchamp, the rebellious Dadaist — with a sense of sense of humour; and Pop Artists like Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and the others.

Thomas McEvilly, like-minded with Dave Hickey, says U.South postmodernism in the visual arts began with the kickoff exhibitions of Pop fine art in 1962, "though information technology took about xx years before postmodernism became a dominant attitude in the visual arts."[xi] Fredric Jameson, likewise, considers pop art to exist postmodern.[56]

One way Pop fine art is postmodern is information technology breaks down what Andreas Huyssen calls the "Nifty Divide" between high art and popular civilization.[57] Postmodernism emerges from a "generational refusal of the categorical certainties of high modernism."[58]

Fluxus [edit]

Solo For Violin • Polishing equally performed by George Brecht, New York, 1964. Photo by Thousand Maciunas

Fluxus was named and loosely organized in 1962 past George Maciunas (1931–78), a Lithuanian-born American artist. Fluxus traces its beginnings to John Cage's 1957 to 1959 Experimental Composition classes at the New School for Social Research in New York Metropolis. Many of his students were artists working in other media with lilliputian or no groundwork in music. Muzzle'south students included Fluxus founding members Jackson Mac Low, Al Hansen, George Brecht and Dick Higgins. In 1962 in Deutschland Fluxus started with the: FLUXUS Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik in Wiesbaden with, George Maciunas, Joseph Beuys, Wolf Vostell, Nam June Paik and others. And in 1963 with the: Festum Fluxorum Fluxus in Düsseldorf with George Maciunas, Wolf Vostell, Joseph Beuys, Dick Higgins, Nam June Paik, Ben Patterson, Emmett Williams and others.[ commendation needed ]

Fluxus encouraged a do it yourself aesthetic, and valued simplicity over complexity. Like Dada earlier it, Fluxus included a strong current of anti-commercialism and an anti-art sensibility, disparaging the conventional market-driven art globe in favor of an artist-centered creative practice. Fluxus artists preferred to piece of work with any materials were at hand, and either created their own work or collaborated in the cosmos process with their colleagues.

Fluxus tin can be viewed as part of the get-go phase of postmodernism, forth with Rauschenberg, Johns, Warhol and the Situationist International.[59] Andreas Huyssen criticises attempts to claim Fluxus for postmodernism as, "either the principal-code of postmodernism or the ultimately unrepresentable art movement – every bit it were, postmodernism'due south sublime." Instead he sees Fluxus as a major Neo-Dadaist phenomena within the advanced tradition. Information technology did not correspond a major advance in the development of artistic strategies, though it did limited a rebellion confronting, "the administered culture of the 1950s, in which a moderate, domesticated modernism served every bit ideological prop to the Cold War."[60]

Minimalism [edit]

By the early on 1960s Minimalism emerged every bit an abstruse movement in art (with roots in geometric brainchild via Malevich, the Bauhaus and Mondrian) which rejected the idea of relational, and subjective painting, the complexity of Abstruse expressionist surfaces, and the emotional zeitgeist and polemics nowadays in the arena of Action painting. Minimalism argued extreme simplicity could capture the sublime representation art requires. Associated with painters such as Frank Stella, minimalism in painting, every bit opposed to other areas, is a modernist motion and depending on the context can be construed as a precursor to the postmodern movement.

Hal Foster, in his essay The Crux of Minimalism, examines the extent to which Donald Judd and Robert Morris both admit and exceed Greenbergian modernism in their published definitions of minimalism.[61] He argues minimalism is not a "dead terminate" of modernism, but a "prototype shift toward postmodern practices that continue to be elaborated today."[62]

Postminimalism [edit]

Robert Pincus-Witten coined the term Post-minimalism in 1977 to describe minimalist derived art which had content and contextual overtones minimalism rejected. His use of the term covered the period 1966 – 1976 and practical to the work of Eva Hesse, Keith Sonnier, Richard Serra and new work past one-time minimalists Robert Smithson, Robert Morris, Sol LeWitt, and Barry Le Va, and others.[45] Process art and anti-form art are other terms describing this piece of work, which the space it occupies and the process by which it is made determines.[63]

Rosalind Krauss argues by 1968 artists such as Morris, LeWitt, Smithson and Serra had "entered a situation the logical conditions of which can no longer be described as modernist."[12] The expansion of the category of sculpture to include land fine art and compages, "brought about the shift into postmodernism."[64]

Minimalists like Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, Agnes Martin, John McCracken and others connected to produce their late modernist paintings and sculpture for the rest of their careers.

Movements in postmodern art [edit]

Conceptual art [edit]

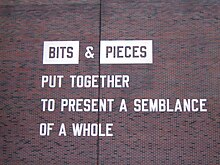

Lawrence Weiner, Bits & Pieces Put Together to Present a Semblance of a Whole, The Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 2005.

Conceptual art is sometimes labelled as postmodern because it is expressly involved in deconstruction of what makes a work of fine art, "art". Conceptual fine art, because it is often designed to confront, offend or attack notions held by many of the people who view it, is regarded with particular controversy.

Precursors to conceptual fine art include the work of Duchamp, John Cage'south iv' 33", in which the music is said to be "the sounds of the environment that the listeners' hear while it is performed," and Rauschenberg'south Erased De Kooning Cartoon. Many conceptual works have the position that art is created by the viewer viewing an object or act equally fine art, not from the intrinsic qualities of the work itself. Thus, because Fountain was exhibited, information technology was a sculpture.

Installation art [edit]

An important serial of movements in fine art which have consistently been described as postmodern involved installation art and creation of artifacts that are conceptual in nature. One example being the signs of Jenny Holzer which use the devices of art to convey specific letters, such equally "Protect Me From What I Want". Installation Fine art has been important in determining the spaces selected for museums of contemporary art in club to be able to hold the big works which are composed of vast collages of manufactured and found objects. These installations and collages are often electrified, with moving parts and lights.

They are often designed to create ecology effects, equally Christo and Jeanne-Claude'southward Iron Curtain, Wall of 240 Oil Barrels, Blocking Rue Visconti, Paris, June 1962 which was a poetic response to the Berlin Wall congenital in 1961.

Lowbrow fine art [edit]

Lowbrow is a widespread populist art movement with origins in the underground comix world, punk music, hot-rod street civilization, and other California subcultures. It is likewise often known past the name popular surrealism. Lowbrow art highlights a primal theme in postmodernism in that the distinction between "high" and "depression" art are no longer recognized.

Performance art [edit]

Digital fine art [edit]

Joseph Nechvatal birth Of the viractual 2001 calculator-robotic assisted acrylic on canvass

Digital art is a general term for a range of artistic works and practices that use digital engineering as an essential part of the artistic and/or presentation process. The impact of digital technology has transformed activities such as painting, drawing, sculpture and music/audio fine art, while new forms, such as cyberspace fine art, digital installation art, and virtual reality, have become recognized artistic practices.

Leading art theorists and historians in this field include Christiane Paul, Frank Popper, Christine Buci-Glucksmann, Dominique Moulon, Robert C. Morgan, Roy Ascott, Catherine Perret, Margot Lovejoy, Edmond Couchot, Fred Forest and Edward A. Shanken.

Intermedia and multi-media [edit]

Another tendency in art which has been associated with the term postmodern is the employ of a number of different media together. Intermedia, a term coined by Dick Higgins and meant to convey new artforms along the lines of Fluxus, Concrete Poetry, Constitute objects, Performance art, and Computer art. Higgins was the publisher of the Something Else Press, a Concrete poet, married to artist Alison Knowles and an admirer of Marcel Duchamp. Ihab Hassan includes, "Intermedia, the fusion of forms, the confusion of realms," in his list of the characteristics of postmodern art.[65] One of the well-nigh mutual forms of "multi-media fine art" is the use of video-tape and CRT monitors, termed Video art. While the theory of combining multiple arts into 1 art is quite old, and has been revived periodically, the postmodern manifestation is often in combination with performance fine art, where the dramatic subtext is removed, and what is left is the specific statements of the artist in question or the conceptual statement of their activity. Higgin'southward conception of Intermedia is connected to the growth of multimedia digital practice such equally immersive virtual reality, digital art and estimator art.

Telematic Fine art [edit]

Telematic art is a descriptive of art projects using computer mediated telecommunication networks every bit their medium. Telematic art challenges the traditional relationship between active viewing subjects and passive art objects by creating interactive, behavioural contexts for remote aesthetic encounters. Roy Ascott sees the telematic art form as the transformation of the viewer into an active participator of creating the artwork which remains in process throughout its duration. Ascott has been at the forefront of the theory and do of telematic fine art since 1978 when he went online for the first time, organizing dissimilar collaborative online projects.

Appropriation art and neo-conceptual fine art [edit]

In his 1980 essay The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism, Craig Owens identifies the re-emergence of an emblematic impulse as characteristic of postmodern art. This impulse can be seen in the appropriation fine art of artists such as Sherrie Levine and Robert Longo because, "Allegorical imagery is appropriated imagery."[66] Cribbing art debunks modernist notions of artistic genius and originality and is more ambivalent and contradictory than modern art, simultaneously installing and subverting ideologies, "being both critical and complicit."[67]

Neo-expressionism and painting [edit]

The return to the traditional art forms of sculpture and painting in the late 1970s and early 1980s seen in the work of Neo-expressionist artists such as Georg Baselitz and Julian Schnabel has been described every bit a postmodern tendency,[68] and one of the kickoff coherent movements to emerge in the postmodern era.[69] Its strong links with the commercial art market has raised questions, however, both nigh its status every bit a postmodern movement and the definition of postmodernism itself. Hal Foster states that neo-expressionism was complicit with the conservative cultural politics of the Reagan-Bush era in the U.S.[62] Félix Guattari disregards the "large promotional operations dubbed 'neo-expressionism' in Federal republic of germany," (an case of a "fad that maintains itself by means of publicity") equally a also easy way for him "to demonstrate that postmodernism is nix simply the concluding gasp of modernism."[7] These critiques of neo-expressionism reveal that money and public relations really sustained gimmicky art world brownie in America during the aforementioned menstruation that conceptual artists, and practices of women artists including painters and feminist theorists like Griselda Pollock,[70] [71] were systematically reevaluating modern art.[72] [73] [74] Brian Massumi claims that Deleuze and Guattari open the horizon of new definitions of Beauty in postmodern art.[75] For Jean-François Lyotard, information technology was painting of the artists Valerio Adami, Daniel Buren, Marcel Duchamp, Bracha Ettinger, and Barnett Newman that, after the avant-garde'southward fourth dimension and the painting of Paul Cézanne and Wassily Kandinsky, was the vehicle for new ideas of the sublime in contemporary art.[76] [77]

Institutional critique [edit]

Critiques on the institutions of art (principally museums and galleries) are made in the work of Michael Asher, Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren and Hans Haacke.

See besides [edit]

- Anti-art

- Anti-anti-art

- Classificatory disputes about art

- Cyborg fine art

- Electronic fine art

- Experiments in Art and Applied science

- Gaze

- Late Modernism

- Modern art

- Modernist projection

- Neo-minimalism

- Net.fine art

- New European Painting

- New Media art

- Post-conceptual

- Superflat

- Superstroke

- Remodernism

- Irving Sandler

- Virtual art

Sources [edit]

- The Triumph of Modernism: The Art Globe, 1985–2005, Hilton Kramer, 2006, ISBN 978-0-15-666370-0

- Pictures of Nothing: Abstract Art since Pollock (A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts), Kirk Varnedoe, 2003

- Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the Early on 1990s, Irving Sandler

- Postmodernism (Movements in Modern Art) Eleanor Heartney

- Sculpture in the Historic period of Incertitude Thomas McEvilley 1999

References [edit]

- ^ Ideas Virtually Art, Desmond, Kathleen K. [i] John Wiley & Sons, 2011, p.148

- ^ International postmodernism: theory and literary practice, Bertens, Hans [ii], Routledge, 1997, p.236

- ^ After the Finish of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History Arthur C. Danto

- ^ Wendy Steiner, Venus in Exile: The Rejection of Beauty in 20th-Century Fine art, New York: The Free Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-684-85781-7

- ^ Post-Modernism: The New Classicism in Fine art and Architecture Charles Jencks

- ^ Clement Greenberg: Modernism and Postmodernism, 1979. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- ^ a b Félix Guattari, the Postmodern Impasse in The Guattari Reader, Blackwell Publishing, 1996, pp109-113. ISBN 978-0-631-19708-nine

- ^ Quoted in Oliver Bennett, Cultural Cynicism: Narratives of Turn down in the Postmodern World, Edinburgh Academy Press, 2001, p131. ISBN 978-0-7486-0936-9

- ^ Fredric Jameson, Foreword to Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition, Manchester University Printing, 1997, pxvi. ISBN 978-0-7190-1450-5

- ^ a b Thomas McEvilly in Richard Roth, Jean Dubuffet, Susan King, Beauty Is Nowhere: Ethical Issues in Art and Blueprint, Routledge, 1998. p27. ISBN 978-90-5701-311-nine

- ^ a b Thomas McEvilly in Richard Roth, Jean Dubuffet, Susan King, Dazzler Is Nowhere: Upstanding Issues in Fine art and Design, Routledge, 1998. p29. ISBN 978-90-5701-311-9

- ^ a b The Originality of the Avant Garde and Other Modernist Myths Rosalind E. Krauss, Publisher: The MIT Press; Reprint edition (July 9, 1986), Sculpture in the Expanded Field pp.287

- ^ James Elkins, Stories of Art, Routledge, 2002, p16. ISBN 978-0-415-93942-3

- ^ Zoya Kocur and Simon Leung, Theory in Gimmicky Art Since 1985, Blackwell Publishing, 2005, pp2-three. ISBN 978-0-631-22867-vii

- ^ Nicholas Zurbrugg, Jean Baudrillard, Jean Baudrillard: Art and Artefact, Sage Publications, 1997, p150. ISBN 978-0-7619-5580-1

- ^ a b Gary Genosko, Baudrillard and Signs: Signification Ablaze, Routledge, 1994, p154. ISBN 978-0-415-11256-7

- ^ Grebowicz, Margaret, Gender Subsequently Lyotard, State University of New York Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7914-6956-ix

- ^ de Zegher, Catherine (ed.) Within the Visible, MIT Press, 1996

- ^ Armstrong, Carol and de Zegher, Catherine, Women Artists at the Millennium, October Books / The MIT Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-262-01226-iii

- ^ William R. Everdell, The Start Moderns: Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth-century Thought, University of Chicago Press, 1997, p4. ISBN 978-0-226-22480-0

- ^ The Citadel of Modernism Falls to Deconstructionists, – 1992 critical essay, The Triumph of Modernism, 2006, Hilton Kramer, pp218-221.

- ^ The Originality of the Avant Garde and Other Modernist Myths Rosalind E. Krauss, Publisher: The MIT Press; Reprint edition (July 9, 1986), Part I, Modernist Myths, pp.eight–171

- ^ The Originality of the Avant Garde and Other Modernist Myths Rosalind E. Krauss, Publisher: The MIT Press; Reprint edition (July 9, 1986), Role I, Modernist Myths, pp.viii–171, Part II, Toward Postal service-modernism, pp. 196–291.

- ^ Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, Avant-Gardes and Partisans reviewed. Manchester University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-7190-4399-four.

- ^ Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon. Routledge, London & N.Y., 1999. ISBN 978-0-415-06700-iii.

- ^ Griselda Pollock, Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts. Routledge, London, 1996. ISBN 978-0-415-14128-4.

- ^ Maria DiBattista and Lucy McDiarmid, High and Low Moderns: literature and culture, 1889–1939, Oxford University Press, 1996, pp6-7. ISBN 978-0-19-508266-1

- ^ Kirk Varnedoe, 1946–2003 – Forepart Page – Obituary – Art in America, October, 2003 by Marcia E. Vetrocq

- ^ a b c General Introduction to Postmodernism. Cla.purdue.edu. Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- ^ Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Art in Theory, 1900–2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Blackwell Publishing, 1992, p1014. ISBN 978-0-631-22708-3

- ^ Michael Forest: Fine art of the Western Globe, Summit Books, 1989, p323. ISBN 978-0-671-67007-8

- ^ Avant-Garde and Kitsch

- ^ Rosalind E. Krauss, In the Proper name of Picasso in The Originality of the Advanced and other Modernist Myths, MIT Printing, 1985, p39. ISBN 978-0-262-61046-9

- ^ John P. McGowan, Postmodernism and its Critics, Cornell University Press, 1991, p10. ISBN 978-0-8014-2494-6

- ^ "Fountain, Marcel Duchamp, 1917, replica, 1964". tate.org.britain. Tate. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Gavin Parkinson, The Duchamp Book: Tate Essential Artists Serial, Harry Northward. Abrams, 2008, p. 61, ISBN 1854377663

- ^ Dalia Judovitz, Unpacking Duchamp: Fine art in Transit, University of California Printing, 1998, pp. 124, 133, ISBN 0520213769

- ^ Tomkins: Duchamp: A Biography, page 158.

- ^ William A. Camfield, Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, Its History and Aesthetics in the Context of 1917 (Part 1), Dada/Surrealism sixteen (1987): pp. 64-94.

- ^ THE INVENTION OF NON-Fine art: A HISTORY ArtForum International

- ^ Simon Malpas, The Postmodern, Routledge, 2005. p17. ISBN 978-0-415-28064-8

- ^ Marking A. Pegrum, Challenging Modernity: Dada Between Modern and Postmodern, Berghahn Books, 2000, pp2-3. ISBN 978-i-57181-130-ane

- ^ De Zegher, Catherine, and Teicher, Hendel (eds.), 3 X Abstraction. New Haven: Yale Academy Press. 2005.

- ^ Aldrich, Larry. Immature Lyrical Painters, Art in America, v.57, n6, November–December 1969, pp.104–113.

- ^ a b c Movers and Shakers, New York, "Leaving C&M", past Sarah Douglas, Art and Sale, March 2007, V.XXXNo7.

- ^ Martin, Ann Ray, and Howard Junker. The New Fine art: Information technology's Way, Mode Out, Newsweek 29 July 1968: pp.3,55–63.

- ^ Interior Scroll, 1975. Carolee Schneemann. Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- ^ [The Living Theatre (1971). Paradise Now. New York: Random Business firm.]

- ^ Gary Botting, The Theatre of Protest in America, Edmonton: Harden Business firm, 1972.

- ^ [Janevsky, Ana and Lax, Thomas (2018) Judson Dance Theater: The Piece of work Is Never Done (exhibition itemize) New York: Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 978-1-63345-063-9]

- ^ [Banes, Emerge (1993) Commonwealth'southward Torso: Judson Dance Theater, 1962-1964. Durham, N Carolina: Duke Academy Press. ISBN 0-8223-1399-5]

- ^ Michael Kirby, Happenings: An Illustrated Anthology, scripts and productions by Jim Dine, Reddish Grooms, Allan Kaprow, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Whitman (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1965), p. 21.

- ^ Douglas Crimp in Hal Foster (ed), Postmodern Culture, Pluto Press, 1985 (first published equally The Anti-Aesthetic, 1983). p44. ISBN 978-0-7453-0003-0

- ^ Craig Owens, Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Civilization, London and Berkeley: Academy of California Press (1992), pp74-75.

- ^ Steven Best, Douglas Kellner, The Postmodern Plough, Guilford Press, 1997, p174. ISBN 978-1-57230-221-1

- ^ Fredric Jameson in Hal Foster, Postmodern Culture, Pluto Press, 1985 (offset published as The Anti-Aesthetic, 1983). p111. ISBN 978-0-7453-0003-0

- ^ Simon Malpas, The Postmodern, Routledge, 2005. p20. ISBN 978-0-415-28064-8

- ^ Stuart Sim, The Routledge Companion to Postmodernism, Routledge, 2001. p148. ISBN 978-0-415-24307-0

- ^ Richard Sheppard, Modernism-Dada-Postmodernism, Northwestern University Press, 2000. p359. ISBN 978-0-8101-1492-0

- ^ Andreas Huyssen, Twilight Memories: Marker Time in a Culture of Amnesia, Routledge, 1995. p192, p196. ISBN 978-0-415-90934-one

- ^ Hal Foster, The Return of the Existent: The Advanced at the End of the Century, MIT Press, 1996, pp44-53. ISBN 978-0-262-56107-5

- ^ a b Hal Foster, The Render of the Real: The Avant-garde at the Cease of the Century, MIT Printing, 1996, p36. ISBN 978-0-262-56107-5

- ^ Erika Doss, Twentieth-Century American Fine art, Oxford Academy Press, 2002, p174. ISBN 978-0-xix-284239-8

- ^ The Originality of the Avant Garde and Other Modernist Myths Rosalind E. Krauss, Publisher: The MIT Press; Reprint edition (July 9, 1986), Sculpture in the Expanded Field (1979). pp.290

- ^ Ihab Hassan in Lawrence E. Cahoone, From Modernism to Postmodernism: An Anthology, Blackwell Publishing, 2003. p13. ISBN 978-0-631-23213-1

- ^ Craig Owens, Beyond Recognition: Representation, Ability, and Culture, London and Berkeley: University of California Printing (1992), p54

- ^ Steven Best and Douglas Kellner, The Postmodern Plough, Guilford Press, 1997. p186. ISBN 978-1-57230-221-ane

- ^ Tim Woods, Offset Postmodernism, Manchester University Press, 1999. p125. ISBN 978-0-7190-5211-8

- ^ Fred S. Kleiner, Christin J. Mamiya, Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, Thomson Wadsworth, 2006, p842. ISBN 978-0-495-00480-6

- ^ Griselda Pollock & Penny Florence, Looking Dorsum to the Hereafter: Essays by Griselda Pollock from the 1990s. New York: Thou&B New Arts Press, 2001. ISBN 978-ninety-5701-132-0

- ^ Griselda Pollock, Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts, Routledge, London, 1996. ISBN 978-0-415-14128-iv

- ^ Erika Doss, Twentieth-Century American Fine art, Oxford University Press, 2002, p210. ISBN 978-0-19-284239-8

- ^ Lyotard, Jean-François (1993), Scriptures: Diffracted Traces, reprinted in: Theory, Culture and Society, Volume 21 Number 1, 2004. ISSN 0263-2764

- ^ Pollock, Griselda, Inscriptions in the Feminine, in: de Zegher, Catherine, Ed.) Inside the Visible. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1996

- ^ Massumi, Brian (ed.), A Shock to Thought: Expression after Deleuze and Guattari. London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-0-415-23804-5

- ^ Buci-Glucksmann, Christine, "Le differend de fifty'art". In: Jean-François Lyotard: L'exercise du differend. Paris: PUF, 2001. ISBN 978-two-13-051056-7

- ^ Lyotard, Jean-François, "L'anamnese". In: Doctor and Patient: Memory and Amnesia. Porin Taidemuseo,1996. ISBN 978-951-9355-55-9. Reprinted equally: Lyotard, Jean-François, "Anamnesis: Of the Visible." In: Theory, Culture and Society, Vol. 21(ane), 2004. 0263–2764

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Postmodern fine art at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Postmodern fine art at Wikimedia Commons

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postmodern_art

0 Response to "What Are Post Modern Values in Art? What Are Postmodern Values in Art?"

Post a Comment